Army West Point Athletics

MISSION FIRST: A Great American Story

January 02, 2015 | Football

Bob Novogratz knows all about being part of something bigger than himself. He grew up in a family of six children. He and his wife, Barbara, have seven of their own. As a member of the "Long Gray Line," he played on one of the finest teams in the history of Army Football. And after he graduated from West Point in 1959, he served his country for 30 years. Easy-going and unassuming, Novogratz speaks in a hushed tone that is just above a whisper. While his personality might be modest, his principles are not. In three decades, he had a number of chances to leave the United States Army, sometimes for more lucrative pursuits, but he always declined."He was too idealistic to get out," says Barbara. "[Whatever jobs he was offered] didn't seem to him to be as important as what he was doing in the Army."

An Infantry officer, Novogratz specialized in logistics, contracting and international programs. He rose to the rank of Colonel, and his final active-duty tours were as the Head of Army Contracting in Europe and as an Assistant to the Secretary of the Army. Along the way, he and Barbara raised a family that has become not only prominent, but also influential. The seven Novogratz children are an eclectic, highly successful bunch.

Jacqueline, the oldest, is the founder and Chief Executive Officer of the Acumen Fund, a non-profit venture capital enterprise with the goal of creating "a world beyond poverty;" she is also the best-selling author of The Blue Sweater: Bridging the Gap Between Rich and Poor in an Interconnected World. Bob and his wife, Cortney, have their own successful design business in New York City and, along with their seven kids, star in the HGTV series "Home by Novogratz." Michael is a principal at the hedge fund Fortress Investment Group. Elizabeth is a freelance writer. John is the Global Head of Marketing and Investor Relations at the Millennium Partners hedge fund. Amy, who was formerly the director of the TED prize - awarded annually at the Technology, Entertainment, and Design Conference - is now a Managing Partner of Aqua-Spark, an investment fund focused on sustainable aquaculture and ocean technologies. Matthew, the youngest, is the director of Foreign Exchange Sales at RBC Capital Markets in New York.

When asked how he and Barbara, whom he married in February 1960, managed to raise a brood of such super-achievers Novogratz pauses to think, and then says, "We don't have a good answer." But Barbara, for her part, is adamant that the size of the family had something to do with it. Bob completed two tours in Vietnam and one in Korea from 1964 to 1971, leaving Barbara on her own for extended periods with the couple's four oldest children.

"They helped each other," she says of her kids. "I told them about their Dad. They knew where they came from. They were part of a tribe."

The son of Austrian immigrants, Bob Novogratz grew up in eastern Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley in the mill town of Northampton, home of the Universal Atlas Cement Company. His father, Frank, was a gruff, taciturn laborer for Universal who spent his days filling bags of cement in the mill's pack house. When Bob was a boy, Frank would arrive home after work covered in the gray dust that hung in the air at the place. Frank Novogratz, with his thick Austrian accent, was a passionate believer in the American ideal, and along with his wife, Stella, he raised his six children to trust in the virtues of hard work and representative democracy. He had been a loyal member of the local chapter of the Democratic Party since the early years of the Depression, when, to earn extra money, he had driven voters to the polls in his Essex Super Six sedan. Bob worked throughout his childhood and held down three jobs when he was in high school, delivering newspapers in the morning, shining shoes in the afternoon, and setting up pins in the evening at the bowling alley attached to the Liederkranz, Northampton's bustling German social club. During the summer, he earned extra money delivering ice.

Novogratz desperately wanted to go to college, but he needed a scholarship in order to afford school. As a skinny, undersized defensive end at Northampton High, he had not been recruited to play college football. Determined to earn his way into a top-flight university, he set his sights on Blair Academy, a prep school in northwestern New Jersey. Two of Bob's older brothers had been good high school players, and two of his cousins who had spent a year at Blair had ultimately earned football scholarships to Virginia. Novogratz worked as a day laborer on the Northampton and Bath Railroad the summer after his high school graduation and scraped together about $3,500, enough to cover most of his tuition. The school also provided him with a small financial aid package when he was admitted in the fall of 1954.

That year at Blair turned out to be everything Novogratz had hoped for. Playing offensive tackle for Coach Steve Koch, he put 40 pounds on his skinny frame. By the spring, he had scholarship offers from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Virginia. But Frank, through his political contacts, had secured him an appointment to West Point. Bob had not been recruited to play football at the Academy, and the appointment was a surprise to him.

"My father had a real cement worker's mentality," says Novogratz. "He was not a very communicative guy, but I knew this was a very big thing to him. Not until later in life did it really occur to me why that was: He was an immigrant, he worked in the mill, and this was an important opportunity for me from his perspective. Him getting my appointment to West Point was probably his proudest achievement."

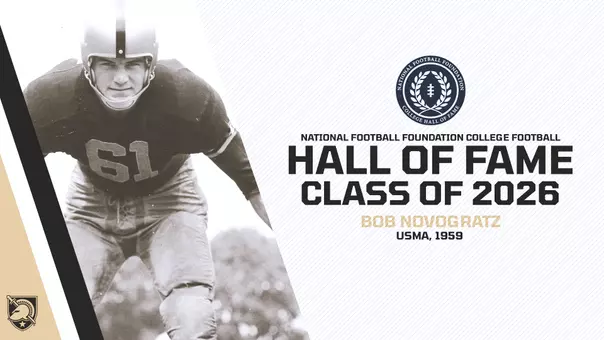

Novogratz had wrestled for the first time at Blair, where his long arms and powerful upper body made him a natural grappler. But two surgeries on his right knee in his first 18 months as a cadet had interrupted his mat career. Novogratz was wrestling as a heavyweight in the winter of his Third Class year when Earl "Red" Blaik, Army's legendary football coach, spotted him during a practice and ordered defensive line coach Frank Lauterbur to "get that kid out for football." Novogratz jumped at Lauterbur's offer, and thus began his meteoric rise to the top of the depth chart: He made the "A Squad" during spring practice, and supplanted classmate Bill Rowe as the starting left guard after Army's opening 42-0 victory over Nebraska in 1957. Novogratz earned All-East honors, but a right ankle sprain hampered him during the bitter loss to Navy at the end of the season.

Novogratz was hardly an unknown entering the 1958 season - when Blaik unleashed his "Lonely End" offense on an unsuspecting nation - though he was usually singled out as the lone returning starter on Army's offensive line. The substitution rules of the time, however, dictated a form of ironman football, and it was on the other side of the line of scrimmage where Novogratz, a linebacker, truly stood out. Blaik described him as the "sword and flame" of the Army defense.

At 6'2" and 210 pounds, Novogratz was quick, aggressive, and prodigiously strong. Indeed, he might have been one of the most powerful players, pound for pound, in college football. He had skinny legs but long, muscular arms that were, in the words of fullback Harry Walters, "like two axes." In addition to being one of the strongest players on the team, Novogratz was an anaerobic marvel who rarely failed to give Blaik more than 50 minutes a game. In Army's 14-2 defeat of fourth-ranked Notre Dame on Oct. 11,1958 Novogratz played 56 minutes in an 18-tackle performance.

The win over the Fighting Irish was one of the highlights of the last truly great season of Army Football. The Black Knights, led by halfbacks Bob Anderson and Pete Dawkins, and end Bill Carpenter - who became a national sensation by splitting at least 10 yards wide of the offensive line on every play and never returning to the huddle - went 8-0-1, led the country in passing offense and finished the season ranked third nationally. Their defense, led by Novogratz, gave up only 5.4 points per game. Dawkins won the Heisman and Maxwell trophies as the best player in college football, and he, Anderson and Novogratz were each named All- America.

"As far as his position," says Rowe, the team's center and nose guard, "Bob was better than Anderson or Dawkins."

Lauterbur - who, before he came to West Point coached All-Pro defensive linemen Eugene "Big Daddy" Lipscomb and Art Donovan with the Baltimore Colts - says that Novogratz was "probably the best allaround defensive player I ever coached."

Novogratz won the Knute Rockne Award, given by the Touchdown Club of Washington, D.C., as college football's outstanding lineman. In late-January, he went to the nation's capital for the awards ceremony, where other honorees included Baltimore Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas and Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown. During the dinner, Brown took a moment to admire Novogratz's trophy, a wooden square base topped by a lineman in a three-point stance, and said, "I dig your trophy, man."

Novogratz had brought his parents to the banquet, and after the meal was over, he was surprised to see his father, whose command of English was not strong, engaged in a friendly conversation with Vice President Richard Nixon. (Frank Novogratz, a lifelong Democrat, cast his vote for Nixon for President in 1960. When his appalled family asked him why he did not vote for John Kennedy, he said, "I never met Kennedy!")

Novogratz is adamant that lessons he learned as a cadet, on the "fields of friendly strife," have been integral to his success at the head of large groups - both in the Army and in his family.

"I learned a lot," he says, "from my gym teachers and coaches about teamwork, cooperation and getting people to do things."

After he retired from the Army, Novogratz continued to work as a consultant on international defense issues. He retired for good in 2008, but he and Barbara are as busy as ever, splitting their time between their homes in Arlington, Va., and Amagansett, N.Y., and shuttling back and forth in support of their children's efforts.

"We never stop," says Barbara. "We're continually doing something."

Both Barbara and Bob have been active in their support of the Acumen Fund, which is run by their oldest daughter, Jacqueline, who cites her father as a source of inspiration. "I think that he always felt as if he'd won the lottery," she says, noting that he was the son of immigrants.

Bob Novogratz may have indeed been lucky, but his idealism has turned that luck into something special - something more than a story of a West Point graduate made good.

"My father came here as an immigrant on a ship when he was 15," says Novogratz. "He spent his life working in a mill. I went to West Point and became a Colonel in the Army. Our seven kids are doing amazing things. Barbara and I think this is a great American story."